S3, E20: The Nature of Our Cities with Dr. Nadina Galle, Part 3

- Jackie De Burca

- November 19, 2024

The Nature of Our Cities with Dr. Nadina Galle, Part 3

“Urban nature isn’t just a backdrop; it’s a daily lifeline for biodiversity, human health, and climate resilience.” – Host, Jackie De Burca

LISTEN BELOW

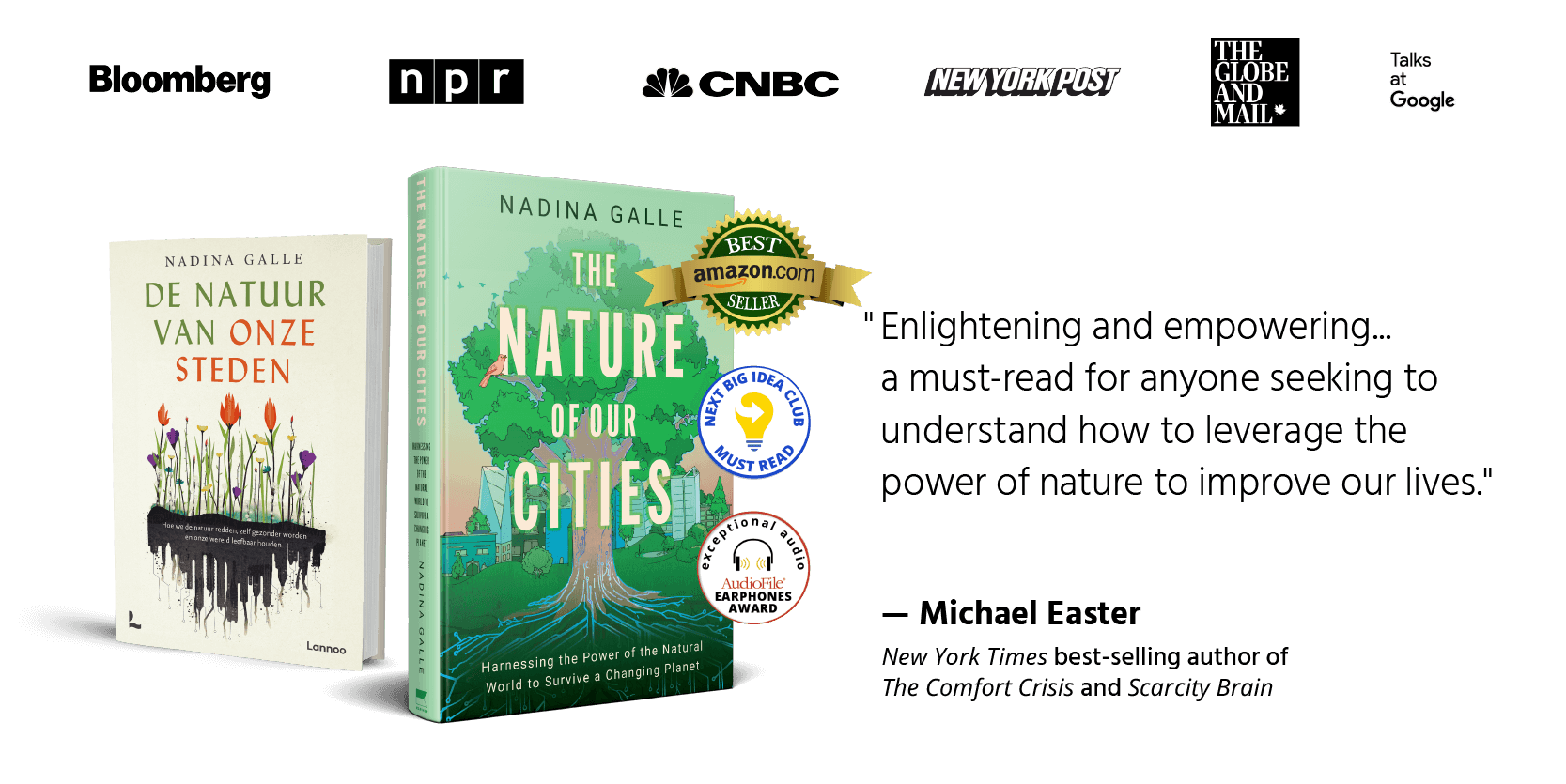

Welcome to the third episode in our special series featuring Nadina Galle, ecological engineer, 2024 National Geographic Explorer, and author of The Nature of Our Cities: Harnessing the Power of the Natural World to Survive a Changing Planet.

Host Jackie De Burca dives into the tools, technologies, and innovations reshaping urban nature management, inspired by Nadina’s book.

In this episode, Nadina tackles:

- Plant Blindness: What it is, why it’s a societal trend, and how it impacts our connection to nature.

- Insect Biodiversity Monitoring: Discover the groundbreaking Diopsis camera, designed to measure flying insect populations and assess biodiversity interventions.

- Urban Evolution: Mind-blowing examples of species adapting to city life, from lighter-colored snails to higher-pitched crows and city-savvy squirrels.

- Citizen Science at Scale: Learn about global movements like the City Nature Challenge and innovative apps like EarthSnap and Merlin, which empower everyday people to connect with and document urban biodiversity.

“Insects may not be charismatic, but they are the fabric of the hammock of life.” – Dr. Nadina Galle

Nadina also shares fascinating case studies that highlight how technology and citizen engagement are transforming how we interact with urban ecosystems.

Key Highlights:

- The term “plant blindness” and its surprising prevalence—even among nature enthusiasts.

- How cities, biodiversity, and urbanization intersect in ways that influence both nature and human health.

- The story of a high school student rediscovering a species thought extinct during the City Nature Challenge.

- Tools like Birdcast and EarthSnap that bring nature to our fingertips and combat flora and fauna blindness.

“The more we understand the flora and fauna around us, the more we care for it—and that’s the first step to protecting it.” – Dr. Nadina Galle

What’s Next:

Stay tuned for the final episode of the series, where Jackie and Nadina explore the connection between human health and daily doses of nature. Learn how urban environments can better support health and well-being through thoughtful integration of natural elements.

Resources Mentioned:

- The Nature of Our by Nadina Galle

- City Nature Challenge (Learn More)

- EarthSnap and Merlin Apps

- Menno Schilthuizen’s Darwin Comes to Town

Listen Below:

Explore More:

Visit Constructive Voices for articles, insights, and updates on sustainable living and urban innovation.

about dr. nadina galle

Nadina Galle, Ph.D. is a Dutch-Canadian ecological engineer, technologist, and podcaster. Her work has been featured in documentaries produced by BBC Earth and in multiple print publications, including Newsweek, ELLE, and National Geographic.

The recipient of several academic and entrepreneurial awards, including a Fulbright scholarship for a fellowship at MIT’s Senseable City Lab, she was selected by Forbes’ 30 under 30 list, and recently named a National Geographic Explorer for her work on how growing cities across Latin America are plugging into the Internet of Nature. She divides her time between Amsterdam and Toronto.

Early Life

Born in the Netherlands and raised in Canada, Dr. Nadina Galle developed a love for the outdoors and a deep commitment to conserving nature from a young age.

Foundational Inspirations & Passions

Inspired by the writings of trailblazing urbanists Jane Jacobs and James Howard Kunstler during her teenage years, she began questioning the imbalance between nature and the urban sprawl she witnessed in suburban Canada.

As an ecological engineer driven by a passion for ecology and a fascination with technology, Dr. Galle researches, develops, and brings emerging technologies to market, aiming to build better communities for both people and nature—a vision she calls the “Internet of Nature” (IoN).

The IoN has since evolved into a global movement, uniting bold practitioners who are leveraging innovative technologies to create nature-rich communities. Dr. Galle’s Internet of Nature Podcast, with over 25,000 downloads, highlights the extraordinary work of these entrepreneurs and innovators, inspiring audiences worldwide.

With over a decade of experience in academia across four continents, Dr. Nadina Galle has a strong foundation in scientific research. Yet, it is her combination of academic expertise and years working at—and building—tech start-ups that sets her apart. She now delivers keynotes, moderates global events, disseminates knowledge, and launches products at the intersection of nature, people, and technology.

Featured In Top Media

Dr. Galle’s work has been featured in documentaries by BBC Earth and arte.tv, on numerous British, Irish, and Dutch radio programs, and in several print publications, including Newsweek, ELLE, and National Geographic, which ran a five-page feature on her Ph.D. research.

She has received multiple academic and entrepreneurial honours, including a Fulbright scholarship for her fellowship at MIT Senseable City Lab, where she continues to hold a research affiliation. Dr. Galle has also been listed on the Sustainable Top 100 of young Dutch entrepreneurs for three consecutive years (the maximum allowed) and was awarded the European Space Agency’s top prize, a “Space Oscar,” for her work on urban tree crown delineation to combat deforestation. Forbes and Elsevier have both recognised her on their respective “30 under 30” lists.

Head In Science, Heart In Communication

Clients, colleagues, and friends appreciate Dr. Galle’s ability to take ownership of results—a quality she attributes to her honesty, empathy, and ingenuity. These traits, she believes, are essential for leading teams to achieve a shared mission.

Passionate about the path she is on—researching and building knowledge to “take nature online”—Dr. Galle takes pride in having her head in science and her heart in communication. She is dedicated to translating academic and technological discoveries into accessible public knowledge across various media.

National Geographic Explorer

In 2024, Dr. Galle was named a National Geographic Explorer, where she is investigating how cities across Latin America are integrating into the Internet of Nature.

Debut Book

Her debut book, The Nature of Our Cities: Harnessing the Power of the Natural World to Survive a Changing Planet, was published by HarperCollins on June 18, 2024, and is available to buy in these places according to where you are in the world.

Digitally generated transcript (may include some errors)

Hello to you. And it is the third episode in this series with Nadine Galle. I am Jackie De Burca. For Constructive Voices. Nadina is going to do a really quick introduction, but the proper introduction about Nadina and her career to date can be found on the first episode of this series where you’ll find out lots of interesting things that she’s done up to date. And she’s going to be doing loads more things throughout her life by the looks of everything. Now we’re covering her book and we split it into sort of three different aspects of the information you’re going to find in her book. And this episode is about the tools and techniques for better urban nature management monitoring. Nadina, you’re really welcome again, thank you so much for being here.

[00:01:02] Nadina Galle: Well, thank you very much, Jackie. Great to be here again. And hello, everybody. I’m Nadina Galle. I am a Dutch Canadian ecological Engineer. I’m a 2024 National Geographic Explorer and most recently the author of the Nature of Our Harnessing the Power of the Natural World to Survive a Changing Planet. And it’s lovely to be back.

[00:01:26] Jackie De Burca: Brilliant, Nadina. So, as I mentioned in the introduction, go to episode one and have a listen if you haven’t already done so. Now, one of the things that really surprised me, Nadina, was to realize that you used to suffer from what’s called plant blindness. First of all, let’s. We probably need you to delve into the exactly what that means. But can you also talk about how you realized that you were suffering at that time from plant blindness?

[00:01:52] Nadina Galle: Yes.

I think it’s kind of funny with plant blindness, this term has been around for a while now, but I saw recently on social media there is this trend now to have all kinds of blindness, whether that be something called blush blindness or a fake tan blindness, this idea that you are doing something and you don’t even realize that you’re doing it. And I think like many people living in cities, despite having a very outdoors childhood, I realized that, you know, walking through my local urban park, that, and I’m ashamed to say this, doing what I do had a really difficult time identifying a lot of plant and insect and other fauna species that I shared my cities with. And of course I’m ashamed to admit this because this is part of my work, but it got me thinking that this is something that I think, especially if you’re, if you’re not an ecological engineer and urban ecologist, like myself, you’re probably, you know, facing this more and more. And I was absolutely disturbed when I discovered this study that was done of both UK and US children that found that the average child was able to identify hundreds of logos and brand names, but not even able to identify 10 local plant or tree species.

And I think that just speaks to such a broader societal trend. Actually, there’s another really interesting research that goes on par with this that found that in the last 50 years there’s actually been less and less references to nature in our music and literature than we had 50 years ago, which I think is something really interesting too. It just speaks to, you know, the role of nature in our day to day society, in our, in our day to day communities. You know, how much do we talk about nature, how much do we reference it and its beauty and its majesty in our songs and in our literature and in our music? How much is it discussed at school and with our young ones? And it got me realizing like if this was something I was struggling with, considering my work, you know, there’s only more and more people that could be facing this. And it’s so critical because I think it speaks this broader trend where we don’t really have a good idea of the role and of nature and that it plays in our day to day life. And as we’ve seen from research, it’s exactly these day to day interactions with nature that we desperately need both for our own health and also for our safety from climate related disasters.

[00:04:34] Jackie De Burca: Absolutely. I suppose the thing that comes into my mind, Nadina, when you’re talking about that is to bring it to the level of like we’ll say a lettuce that, you know, you might use in a salad. Like a lot of the kids that I would interact with, I don’t have my own children, but you know, obviously lots of friends do and they would see that you get a lettuce from the supermarket. So it’s like nature is just taken out of the equation as to where, you know, where our food is even produced.

[00:05:00] Nadina Galle: Right, right, exactly. I mean, there’s kids that grew up in cities that think that milk comes from the supermarket. They don’t even make the association with a cow. So it really goes to show how far removed we’ve become. And you could argue like, who cares? Who cares that kids don’t know about that? Why is that even important? And I would argue it gets at the most existential, deepest roots of what makes us human, our connection to the earth and the food that we e and the Air that we breathe and the resources that we use, they all stem from the earth in one way or another. And once we’ve completely lost touch of that, well, I honestly really fear for the future of humanity in that sense.

[00:05:44] Jackie De Burca: Yeah, absolutely. And again, just as you’re talking, Nadine, it comes into my mind if you think about the cave art, you know, the art that you see, prehistoric art in caves, this was of animals, normally, not all of it, but a lot of it is of animals. So, you know, when we think about it, it’s only maybe 200 years or so of industrialization and then going forward from there, how that’s affected society. But before that, all of our ancestors were involved in nature on a daily basis. Normally.

[00:06:21] Nadina Galle: Yeah. And I think that’s why the role of city nature is so important, because as we. We as ancient humans experienced in those days, nature was very much a part of our daily lives. And I think we’ve gotten to the point where we feel we can get, you know, fill up our nature cup on the weekends or on holidays with a trip or with a hike. And more and more research shows us that the real benefits of nature comes from those daily doses and that it doesn’t have to be these, you know, vast expanses of wilderness. Don’t get me wrong, those are incredible if you have the opportunity to visit. But getting a lot of these daily doses could come from a singular tree that is planted from outside your house, where you see the wind rustling through the leaves, where you hear the birds singing, where you see the ants climbing up the trunk. Like you, you have these, these daily doses. That is honestly really what makes up the majority of our lives.

[00:07:17] Jackie De Burca: Yeah, no, I entirely agree with you. And I’m lucky enough, you know, that I can access that. But of course, some people, it’s. It’s not so easy to do. One of the things that strikes me as being harsh but true, I suppose, is urban living equals, you know, unprecedented biodiversity loss, but also strong biodiversity protects environment and human health. Now, that actually leads us on to the fact that there’s been huge declines of obviously, all sorts of populations, but particularly the insect population. Can you talk us through this, Nadine? And you know how it affects us?

[00:07:56] Nadina Galle: Yeah, it’s interesting because we can also see around the world that some of the world’s biggest cities are actually started and have grown in some of the world’s largest biodiversity hotspots. And I think that just says something is like, well, why are we drawn to biodiversity? Why do we want to settle in places that have High biodiversity. And I think we know that the more biodiversity, the more buffer we have from different natural disasters, the more opportunities, the more itches that we have to potentially exploit for different shelter resources. Medicines is a huge one, building materials, different food types. You know, we want to live in places that are abundant with life and abundant with a variety of life. So I think it’s interesting that in the course of human history, we’ve already been drawn to these biodiversity hotspots to create our cities and grow our cities. But of course, the way that we go about urbanization is also incredibly dangerous to biodiversity. It leads to habitat fragmentation, which is arguably the biggest threat to biodiversity itself when you’re removing habitat. And of course that fragmentation means that, you know, you’re losing areas of natural migration, you’re losing larger ranges for certain species of animals to be able to hunt or to gather their own resources.

And particularly one of the species that’s most effective is our insect population, as you mentioned, Jackie. And you know, people often wonder, it’s like, well, you know, why would I care about insects? I care about elephants and tigers. And I understand that insects might not be the most charismatic of species that we have, but they are, in fact, they make up the fabric of the hammock of life. They are at the very essence, you know, they are the world’s biggest pollinators, which of course, is critical for food supplies. They are the biggest scavengers. You know, they ensure the decomposition of organic matter that goes back into the soil and returns as new forms of life.

And they offer this wonderful litmus test or this biomarker for biodiversity as a whole. So what we see in areas that have decreased biodiversity, insect populations were actually the first to go. So you have this relationship where if insect populations decline, biodiversity as a whole declines. So it only makes sense that we really want to monitor and manage our insect populations to be able to provide a proxy for the management of other biodiversity. But the issue was in the past is that we lacked objective means to measure insect populations.

And I mean, the reasoning is quite simple. Insects are quite difficult to measure and to count.

And we have, you know, we’ve had multiple kind of citizen science initiatives that have helped somewhat, but they lack a certain, you know, they’re all quite subjective. So really the market was ripe for an objective means of measuring insect populations so that we have this proxy for biodiversity as a whole.

[00:11:09] Jackie De Burca: So let’s talk about the story behind the state of the art insect biodiversity monitoring and how this actually functions.

[00:11:18] Nadina Galle: Yeah, so that’s a story that I cover in the book called the Diopsis camera. And the Diopsis camera is essentially a solution for this problem. This problem I just outlined trying to devise a.

It’s. It’s basically, it looks like a small table. And on top of that table that you would put either in a meadow or on an agricultural field, or on top of a rooftop in a city anywhere where you wanted to measure the insect populations, it essentially is this small metal table. On top of it, you have this protected from the elements camera, and then you have this yellow landing pad. The reason it’s yellow is that yellow is a color that tends to attract a lot of flying insects. So this camera, essentially how it works is it takes a photo every 10 seconds, and every time there’s an insect on that yellow landing pad, it immediately runs through the computer vision algorithm to identify not only the species of that insect, but also measure its biomass. And in that sense, we get a really objective means of measuring flying insect populations, which, of course, is already one of its limitations. It only looks at flying insects, but it is one of the best means that we have right now to initially measure insect populations. But secondly, also, hopefully, I would say the main use case of this is to analyze if money and investment, and there’s a lot of it recently that’s being poured into biodiversity measures and interventions are actually working because that, I think, you know, biodiversity feels so vague and so abstract. You know, how do you even go about making sure that the money that you’re pouring into it is actually helping? This is. This is one way to do that.

[00:13:09] Jackie De Burca: Yeah, that’s really important. I mean, obviously, whatever funds or companies, you know, that are investing in this, they want to see some sort of returns and be able to, you know, discuss that with within their own boards and obviously if they have, you know, shareholders and investors and so on. So it’s critical, really, isn’t it?

[00:13:30] Nadina Galle: Yeah, and it’s mostly. I mean, a lot of these. It’s government spending, so it’s all taxpayer money. So, you know, people want to make sure that in an era with so many different competing interests, just even in the environmental and climate front, that we want to make sure that we’re spending our money wisely.

[00:13:46] Jackie De Burca: Something else that was very curious. We see ingenious adaptations by birds and mice on one hand, which I found really fascinating. But also on the other hand, there’s new diseases and new dangerous behaviors of other creatures. Now, for example, one of the case studies that you speak about in the book is the discovery of the lighter color of Some snails, which has happened because they’ve adapted to their environment.

How was this discovered and what tools are now available in relation to this area?

[00:14:21] Nadina Galle: Yeah, so this is, this is bizarre, this idea of urban evolution. This has really been popularized by a Dutch scientist, an entomologist originally, but he’s an evolutionary biologist in the broader sense of the world word. His name is Menno Schildhausen and he works at the biodiversity museum and center called Naturalis in the Netherlands in Leiden. And he has looked at so many different examples of this phenomenon, which he calls urban evolution. And so that could take essentially what it is. We previously thought that Darwinian evolutionary, we would not be able to see that in a human lifetime. Right. We can’t see evolution happen. Which was, you know, one of the core reasons that Darwin had so much trouble popularizing his theories. Because people had a hard time believing that this could happen because they couldn’t see it with their own eyes. And what we’re seeing with urban evolution, in the shorter lifespans of species like certain insects and like birds and like certain plants, we can actually see evolution in real time, as Mennosculfeizer puts it. So an example of this would be that in cities there are certain plant species that have actually evolved to drop their seeds closer to the mother plant than in previous evolutionary cycles. Where those seeds, you would actually want them to be lighter and more easily catch the air so that they could disperse wider. Right. Because that is the ultimate goal of evolution, is to disperse your specific species as wide as possible and exploit as many niches as you can. And this particular plant species has actually evolved to drop its seeds closer to the mother plant. Because in, you know, asphalt, concrete ridden cities, you’re more likely to establish if you drop closer to the mother plant, because we know that that plant has been able to root in some soil versus yeah, you can disperse very far. But if those seeds, you know, land on asphalt or on street, they’re obviously not going to be able to succeed.

So that’s a pretty crazy one. Another one is crows that have actually started to vocalize at much higher frequencies so that they can actually hear each other over the sounds of traffic, which is really, really crazy to me.

[00:16:47] Jackie De Burca: You have, it’s amazing.

[00:16:49] Nadina Galle: So it’s so cool. And there’s, there’s, I mean, so Menuscule wrote this and incredible book, one of my favorites called Darwin Comes to Town. It’s such a good title. And he has essentially, it’s a book chock full of exactly these kinds of examples. And I Could keep going because they’re just so fascinating. But one of the ones.

[00:17:08] Jackie De Burca: Go on, tell us more. Definitely one of them.

[00:17:14] Nadina Galle: One of these other ones that I think is so wicked too is like the coloring of squirrels. So you squirrels have actually been. So you had in. So where I grew up in southwestern Ontario, you have the eastern gray squirrel and you also have a slightly darker variety. So where I grew up, like in a much more forested area, like you would always see the gray squirrels, like that was the most popular one. You would see that all the time. And then when I was 18, I moved to Toronto to study for my bachelor’s and you would see gray squirrels sometimes.

Most of the time you saw these really like a much darker, almost black variety of these squirrels. So I started looking into that. And evolutionary biologists had seen that these black squirrels were coming more and more popular in city environments because you could see them better against the grayscape that is our cities. So gray squirrels essentially were more likely to become roadkill in cities purely because of their color. Because you can see them as well versus these black squirrels, they stood out more. So there’s more of these black squirrels. So it’s just examples like that. It’s just, it’s bizarre because you can actually, like I said, you can see this in real time. You can see this over the course. And one of the examples that Menno was really interested in was this coloring of snails, specifically this, this model organism that’s used in a lot of different ecology research. Ecological research called it. I mean, it’s basically like your typical garden snail. And basically how he wanted to study this, and this is how a lot of urban evolution cases have been studied, is through the use of tons and tons of sampling. Because you want to make sure that this is not just a one off, right? You want to make sure that you can actually are able to tell evolutionary trends with a huge amount, you know, more samples the better.

But what do you do? You know, you can hardly send out an army to get all of these different samples of these different plants and pick photos of squirrels and snails. So they use the power of citizen science and they designed an app called Snail Snap and they essentially invited people all over different cities in the Netherlands to take photos of this specific type of land snail. And that worked quite well because they’re quite well known, they’re easy to rectify, recognize, and they also don’t move that fast, so they’re easy to photograph. And they collected something like, I think it was 8,300 geolocated and that was really important. Geolocated images of these snails. And they again ran them through a computer vision algorithm, and they were able to see that the snails that were in dense city centers on average, actually had lighter shells than those that were outside of city centers.

Basically, this garden snail is now evolving into these two different varieties. And the one that lives in dense urban cores actually has a lighter shell because it’s able to then deal with extreme heat better, with temperatures better. And I thought this was so interesting because essentially what it’s done is it’s made the color of its house, of its roof, lighter. And this is actually a mechanism that we see also humans do. When we’re not able to implement a green roof on our buildings, one of the most cost effective things we can do is actually paint our roofs white so they’re better able to reflect the light and therefore keep our homes a lot cooler too. So it’s just funny, one, to see the power of citizen science in this, two, to see that snails are actually evolving in this way, and three, things that us humans can actually learn from snails.

[00:21:01] Jackie De Burca: It is absolutely amazing. It’s really fascinating stuff, Nadina, when you think about, like, both the squirrel and the snail that you’ve just spoken about, like, they have to evolve and have to somehow or other change their pigment. Pigmentation, essentially.

[00:21:17] Nadina Galle: Yes, yes. To survive. And that’s the crazy thing. It’s like. And of course, it. It is evolution. Right. So essentially what that means is that snails that have had darker colored shells have tended to perish quicker than those that have lighter colored snails. So those are perishing. That means that the lighter colored varieties have more chance to reproduce. And over time. And of course, you know, snails have shorter lifespans over time, which is more rapidly. In a human lifespan, we’re actually able to see that the vast majority of the snail population then has lighter shells.

[00:21:51] Jackie De Burca: Yeah, absolutely. So such fascinating case studies that you’re sharing in the book. There are other great tools as well that you feature. One is called birdcast, and the other is earthsnap. What are they and who created them?

[00:22:07] Nadina Galle: Yes. So Earth Snap was. I’ll start with that one, because it’s similar to Snail snap in the sense that it is able to identify species. Although Earth Snap doesn’t just do that for snails, it does that for millions of flora and fauna species around the world. The inventor is Eric Rawls. He’s originally from Texas, now lives in Colorado. And he originally started with something called earth.com, which was his main goal in life, was to create this massive repository of photos and observations and information about every single species on Earth. That was his goal. Based on that information, he then started something called PlantSnap, which was, is still to this day, one of the best plant identifying apps on the market.

But after the success of Plant Staff, he wanted to go even bigger, and he decided to open up the entire earth.com repository to creating an all in one plant, you know, flora and fauna identifying app. And he’s now working very hard to grow that app. And he hopes, I mean, much like an app called Inaturalist, which is also used very widely and also much for scientific research, he hopes that this is something that we started the conversation with, can really help to combat that thing that we call plant blindness. Because I do believe that it all starts with just knowledge and awareness and understanding. The more that we can understand what grows and what lives around us, the more we understand about it, the more we can care for it and the more we’ll do, hopefully, to protect it. So that’s Eric Rawls and Earth Snap, and then Birdcast was actually developed by researchers at Cornell University together with something called Merlin. Merlin is another app that is actually. It’s like a Shazam for birdsong. They’re actually able to identify birdsong based just on birdsong. You have a recording of that or you play it live or record it live, and it is actually able to recognize that and hopefully identify what bird that song belongs to. And this is just such an innovative way of doing it. Because, of course, as you can imagine, with things like, with an app like Earth Snap, plants easy to photograph. They don’t move. Certain animal species. Also easier to photograph birds, Very, very difficult. So to have something like Merlin is really, really exciting because it’s also able to. You know, what we’re able to do then is we’re able to take recordings in the middle of a park, in the middle of a forest, in the middle of a rooftop garden. We’re able to take these recordings and based on those recordings, were able to actually identify which birds are in that area. And the way that they specifically do it with artificial intelligence is really interesting. They don’t do it purely on the audio recording. What they actually do is they convert that audio recording into, I believe it’s called a. Is it called a sonogram, where you have, like, a visual depiction of that audio? And based on that, okay, they’re able to run their artificial intelligence and basically identify, okay, which sonograms are most similar to each other and which are most likely to belong to that specific bird. Again, none of these apps are perfect. None of them are a replacement for, you know, a die hard bird watcher or a die hard naturalist, of course. But I think they’re just a beautiful way to facilitate those first interactions with nature and with certain species that we live amongst that people might not otherwise be able to have.

[00:25:42] Jackie De Burca: Sure. No, no, no, absolutely. And again, you know, you trigger thought processes as you’re. As you’re talking through all of this. And I wonder, I know we’ve got a small bit of an age difference, about 20 years or a little bit more, I think.

But I wonder, Nadina, did you experience the same in terms of your family going back to your grandparents where it was normal in Ireland? Certainly for me, for my grandmother to have spoken about, like, natural, natural plants that might heal something, some element of some sort. So it’s not that far. It’s not that far back is what I’m trying to say, since, you know, it was relatable to think about plants as medicine.

[00:26:23] Nadina Galle: Yeah, absolutely. And I think, I mean, my grandmother worked much the same way, and even my mom did to a certain degree. And that’s something that I do believe is. Has been lost in, let’s say, the Gen Z millennial generation, or even further back than that. But I do see this huge resurgence. Like, I think there’s a ton of interest in rediscovering, you know, how do we make meals from scratch? I mean, look at just the sourdough bread revolution that we saw during COVID when everybody started making their own bread at home. I mean, that was, that was something that was really, really commonplace, you know, quote unquote, back in the day that we’ve, you know, we kind of. We’ve completely lost that skill because no one taught it to us, because our mothers or our fathers have lost that skill in the same way that like, you know, much of, like, sewing has, you know, gone, you know, gone by the radar or things like, you know, basic, basic, like bicycle repairs or basic, you know, electronics or appliance repairs.

You know, we’ve kind of lost in our, you know, our world of consumerism and how easy it is to replace different things and our obsession with everything new and having updates to these, you know, these technologies and these things. I think we’ve lost sight of that. But I do believe that there’s this huge resurgence. And you see it in things like people wanting to homestead, even in, you know, dense urban courts, people wanting to grow their own food, even on balconies, a new kind of resurgence in hunting and in like outdoor wilderness exploration and survivalist hunts. Like, I do feel like there’s this huge kind of resurgence in interest in those things as well as homemaking. And I do think that that is really beautiful because so much of that knowledge, one, I think makes our lives a lot more pleasant and a lot more beautiful to be able to also pass down that kind of wisdom and knowledge. And ultimately, I think nature has a lot of the answers. We just kind of have forgotten how to listen.

[00:28:28] Jackie De Burca: Absolutely, absolutely. So that leads me on Nadina to chapter six. And I really love the title you gave the scientist within us, which really is amazing in terms of encouraging citizen science, science and involvement.

So we’ve kind of touched on that in some levels. What is the global urban wildlife exploration through the City Nature Challenge?

[00:28:56] Nadina Galle: Yeah, I absolutely love this example of the City Nature Challenge because I think so much when these monitoring tools and technologies, you know, they often stay in the ivory tower of academia and it feels difficult for your average citizen to take part.

And what the City Nature Challenge does is it actually invites urban nights from all over the world every single year in this four day BioBlitz. It’s typically at the end of April, beginning of May, and it started in 2016. So they just had their ninth edition in 2024. And it started as a simple rivalry friendly, ish competition between Los Angeles and San Francisco. It was organized by the California Academy of Sciences and the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History. And it was meant to use the app inaturalist as a way to get citizens involved in these cities to basically photograph, identify and upload as many observations of local biodiversity within the city limits to inaturalists as possible.

And this basically took off. It got more and more people involved every year. It grew from something that was only in these two cities to something that was only in California, to something that was only in the US to something that has now just taken over the world. In the past edition in 2024, over 700 cities took part.

I actually got to be a part of it in la, not the capital, but the largest city in Bolivia. La Paz has actually been crowned the winner of the City Nature Challenge for the past three years in a row. I got to be there with my National Geographic Explorer hat on, producing a document documentary about the City Nature Challenge and what has led La Paz to these victories.

And there’s a couple things that I learned. One, lapasse is one of the world’s most biodiversities. Right. So that makes winning something like this in terms of most species identified and the most observations made a little bit easier. But La Paz also won for having the most people involved, involved, which is something that every city, of course, can compete in. And one of the ways that they were their secret weapon, if you will, that they were able to do this is they had a local organization, the Bolivian chapter of the Wildlife Conservation Society, get really involved and use their connections to involve almost every single high school and university and college in La Paz. So in these four days it is because it usually takes place. There’s a Friday and then there’s a Saturday, Sunday, and then there’s the Monday. So on the Friday and the Monday, they don’t have school. Their school for that day is to go on a guided field trip to different national park, different parks, even on a street, like all these different areas that they designate. And they send buses full of students to these different areas on these field trips to go and identify as many species as possible. And then they have this as part of their curriculum for that season where then they actually do projects based on the observations that they made. And I met this incredible biology teacher, Ms. Gladys. And Ms. Gladys, the biology teacher, she says to her students, like, it is not the end of your school day until you identify at least 200 not species, until you make at least 200 observations. And of course you get more points. You do. So again, what we started this conversation with Jackie, this idea of plant blindness and I would say kind of flora and fauna blindness as a whole. What you’re doing is you’re taking youth kids out into their cities, the places where they live, where they grow up, where their families are from every single year in this beautiful celebration of urban wildlife. And you’re asking them directly to get involved, not only by taking their observations and learning about it, but also understanding what grows in their area and getting excited about in a way that they can then tell their families and hopefully their children about it in the future.

And it’s just such a beautiful way because urban nature already fights for that kind of recognition that it deserves. And what I love about this is this four day BioBlitz. It’s almost like a holiday, a celebration of urban nature every year. And kudos to Allison Young and Lila Higgins, who initiated and started this challenge all those years ago.

And I know speaking to Alison Young, she is blown away by how far it’s gotten, the wide reaching places that it’s gone to, and the amount of people that get involved year over year. It’s really quite something.

I’ll just Name two favorite discoveries that I learned in the past. One was the Bolivian snake, which actually was thought to be extinct in La Paz. It actually hadn’t been seen really for over 40 years. It had not been seen and it was rediscovered by a high school student during the City Nature Challenge. They got a photo of it.

[00:34:15] Jackie De Burca: So that’s just amazing. Imagine how the student must have felt.

[00:34:20] Nadina Galle: It was shocking. I mean, similar story happened in, I believe it was West Virginia. It was a pill bug that also was the same kind of story. You know, thought to be extinct, hadn’t been seen in decades by researchers, was also discovered by a 15 year old student who her dad describes as being like totally phone addicted. You know, she didn’t want to do it and her dad kind of made her do it with his phone, blah, blah, blah. She goes, and she takes a photo of this pill bug. She completely has this like life altering moment. She goes to cheap. Not only does she publish academic findings together with people from the California Academy of Sciences in a peer reviewed science journal before she graduates high school, but she actually went on to study zoology as well.

[00:35:02] Jackie De Burca: That is just such an amazing story. And obviously, yeah, you can imagine that there’s children or young people whose lives are turned around purely through this city Nature challenge.

[00:35:16] Nadina Galle: Oh yeah. I mean there’s just, there’s, there’s so many examples of that in the book as well. Like there’s another one with the Heat Watch campaign which we discussed. I believe it was in episode two, this idea. We can do these hyper local measurements of heat and ambient temperature in your neighborhood so that you can form better greening policy and better cooling strategies. There was this, there was a student there because they try to involve high school students as much as possible on that project as well. There was a high school student that through that Heat Watch campaign discovered that his house on average was like 10 or 15 degrees hotter than his friend’s house. And he was like, well that makes sense because we always go and play there in the summer because it’s so much cooler in his backyard and on his street than it is online. He was, he was so inspired by this. He was actually on the, on the cusp of dropping out of school because his family was going through financial hardship and he wanted to drop out of school and work in a store to help out his family. And the founder of Heat Watch, Vivek Shonda, has got in touch with the student and actually started mentoring him. And now he’s actually in an undergraduate program for environmental sciences. And Vivek just Kept saying, I believe I wrote this in the book that like he can’t wait to hire him when he graduates because he did so inspired by the story. And it just goes to show, like, there are so many beautiful, you know, this is, this is bigger than just changing, you know, our environments and where we live. But there’s, there’s also beautiful career opportunities for our young people here. And we’re going to need this next generation of, you know, Internet of nature innovators or techno ecologists to really, you know, lead this avant garde. And it’s just amazing to see initiatives like this make that difference.

[00:36:59] Jackie De Burca: It absolutely is. I had a call yesterday from a lawyer based in England regarding the biodiversity net gain law that’s obviously come out earlier in 2024, in February there. And that is just connected with the fact that he had a business idea to do with that. And we have a course that we’ve developed on that. And all of this is based on the fact that there is not anywhere near enough ecologists to go around just to handle that particular law. So it’s a tiny little example of what you’ve said correctly, Nadina, which is that this generation coming up now, there’s like wonderful opportunities for them to be massive change makers and involving themselves in nature, as you say, you know, with, with the combination with technology, which is of course exactly what you talk about, you know.

[00:37:52] Nadina Galle: No, that’s the thing. And, and we’re going to need them. I mean, we needed them yesterday and we definitely need them now. So I, I think what’s amazing about this is it’s kind of the next generation of young people that are die hard environmentalists and nature lovers at heart, but also see the power that technology can help, you know, win over people that need to be won over still and also help them in their work. I think that’s going to be quite critical. I see myself having to do less and less convincing about the powerful ways that technology can help us in this fight and more have that be something that’s second nature.

[00:38:32] Jackie De Burca: Absolutely. I think, I think that should be the case. Hopefully, Nadine, as you say now, we’ve covered a lot again, which is brilliant and we’ve one more episode for our listeners to look forward to which is going to be focused very much around health and health strategies and practices about integrating daily doses of nature, hopefully for those people who can manage it and how that can affect human health. So obviously looking forward to that and we’ll be chatting again very soon. Nadina, thank you very much.

[00:39:02] Nadina Galle: Thanks, Jackie.